Last week, I pointed to skyrocketing rents as one reason that so many Americans are living with their parents into their 20s and 30s. But relief may be on the way for millennials and their beleaguered parents: Rents may, at last, be cooling off, especially in the most expensive cities.

Don’t break out the champagne — or the moving boxes — just yet. So far the biggest slowdown in rents is confined to the most expensive apartments in the most expensive cities. But there’s reason to think the trend will eventually reach the broader market.

On Wednesday, Equity Residential, a big apartment landlord with buildings in more than a dozen U.S. cities, warned investors that revenues would be lower than expected because of softening rents in New York and San Francisco. It was the second time this year that the company had to cut its forecasts — and it isn’t alone. Appraisal firm Miller Samuel Inc. reports that to lure tenants, a growing share of Manhattan landlords are being forced to cut prices or to offer concessions such as a free month’s rent. Median rents in Manhattan (for all unit sizes) fell in March for the first time in two years before rebounding somewhat in April.

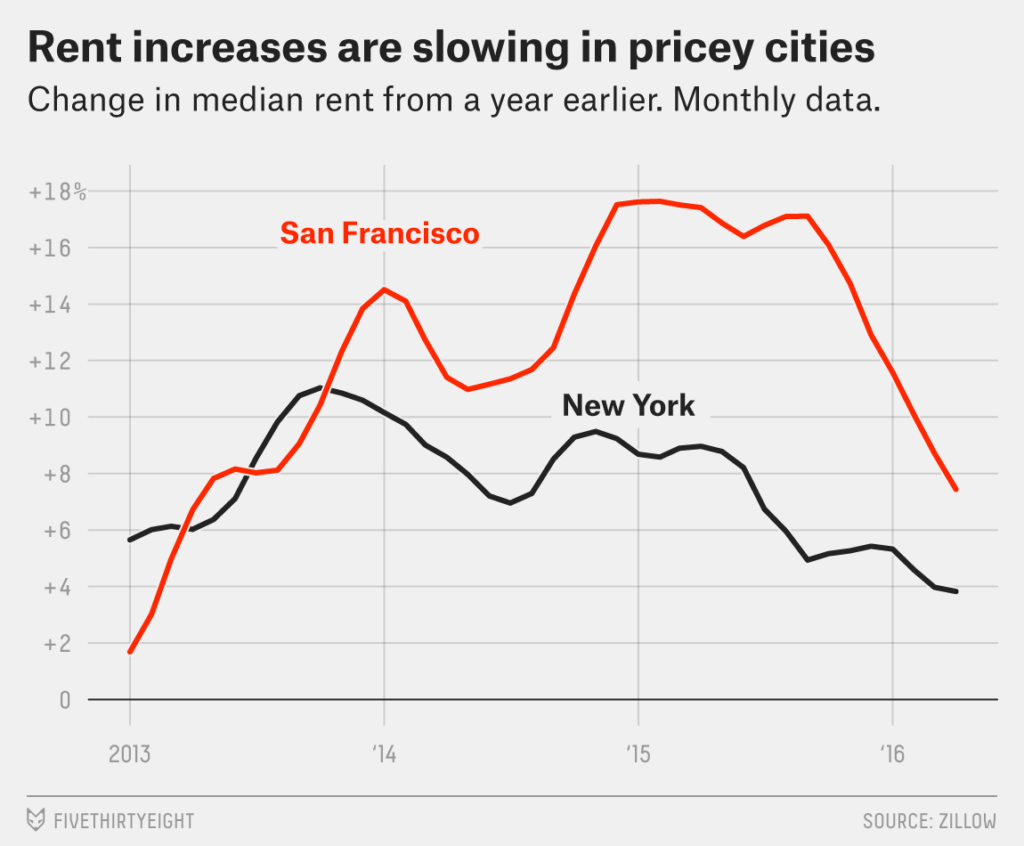

Rents are still rising faster than inflation in most of the country, and they are accelerating in cheaper markets such as Las Vegas, Dallas and Jacksonville, Florida. But the slowdown in many of the most expensive markets has been striking. A year ago in New York, rents were rising at an annual rate of 9 percent, according to an index compiled by the real estate site Zillow; in April, they were up 3.8 percent. In Los Angeles, rental growth slowed from 9.2 percent last year to 5.7 percent this year. Even in San Francisco, home to the country’s highest rents (and fiercest rental battles), the growth rate has slowed to 7.4 percent from more than 17 percent a year ago.1

| CHANGE* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RANK | CITY | MEDIAN 2016 RENT* | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 |

| 1 | San Francisco | $4,535 | +17.4% | +7.4% |

| 2 | San Jose | 3,347 | +16.8 | +9.8 |

| 3 | Los Angeles | 2,631 | +9.2 | +5.7 |

| 4 | Boston | 2,499 | +3.1 | +1.8 |

| 5 | Seattle | 2,429 | +8.0 | +12.1 |

| 6 | San Diego | 2,410 | +7.0 | +4.8 |

| 7 | New York | 2,335 | +9.0 | +3.8 |

| 8 | Denver | 1,961 | +10.4 | +8.2 |

| 9 | Austin | 1,789 | +8.3 | +2.7 |

| 10 | Chicago | 1,682 | +3.4 | +0.9 |

| 11 | Houston | 1,444 | +7.8 | +3.5 |

| 12 | Fort Worth | 1,345 | +5.0 | +3.7 |

| 13 | Baltimore | 1,343 | +3.6 | +3.5 |

| 14 | Dallas | 1,335 | +4.1 | +5.5 |

| 15 | Charlotte | 1,274 | +5.1 | +4.1 |

| 16 | San Antonio | 1,244 | +5.8 | +4.1 |

| 17 | Phoenix | 1,227 | +5.9 | +5.5 |

| 18 | Las Vegas | 1,221 | +1.6 | +3.9 |

| 19 | Philadelphia | 1,204 | +6.3 | +2.3 |

| 20 | Jacksonville | 1,157 | +2.1 | +2.2 |

| 21 | Columbus | 1,126 | +10.4 | +3.0 |

| 22 | Indianapolis | 1,066 | +1.4 | +0.9 |

| 23 | El Paso | 1,026 | +1.2 | -1.8 |

| 24 | Memphis | 849 | +0.4 | -0.7 |

| 25 | Detroit | 754 | +0.1 | +0.1 |

*As of April

SOURCE: ZILLOW

What’s behind the slowdown? Supply and demand. Developers have been on an apartment-building spree in recent years, and those buildings are now coming online, flooding the market with new units. In its press release Wednesday, Equity blamed “new rental apartment supply” for its lowered expectations. Miller Samuel estimates that apartment inventory is up 23 percent in Manhattan and 16 percent in Brooklyn in the past year. Meanwhile, demand may be hitting its limits: Miller Samuel President Jonathan Miller said some New Yorkers are buying in the suburbs rather than continuing to struggle to pay rent in the city.

“Consumers, after a number of years of rising rents, are going through some sort of affordability threshold where they start considering alternatives,” Miller said.

Affordability is unlikely to improve quickly. Most of the buildings coming online are at the top end of the market. As a result, rents for luxury buildings are leveling off or even falling, while rents continue to rise in the lower and middle tiers of the market. Eventually, the high-end slowdown should filter through to the rest of the market, as wealthier renters move into expensive new buildings, reducing competition for older apartments. (In time, the new units will also become less desirable and therefore more affordable.) But market forces work slowly. Miller said he expects “more of a slow bleed than some sort of overnight correction.”

The process could move faster if developers were building more apartments targeted at lower- and middle-income renters. But as Daniel Hertz has written, U.S. cities are building mostly single-family homes and high-rise apartments — leaving a “missing middle” of small apartment buildings that were once a key source of affordable housing. That’s at least partly the result of zoning codes that discourage such building.

Still, even without major policy changes, the runaway rents of the past few years look like they have come to an end. Zillow expects 3.3 percent growth in rents nationwide over the next year — modest compared with the 5-plus percent seen much of last year — and many expensive cities, including New York, should see milder increases. That won’t by itself reverse the affordability crisis that now plagues many U.S. cities, but at least it might give renters some much-needed relief.

Mandatory minimums

The surprisingly successful battle for a $15 minimum wage has been waged, to a large degree, at the city level. Seattle, Los Angeles and other cities around the country have adopted minimum wages higher than their states require. But now states are pushing back against such moves.

The Wall Street Journal reported this week that states including Alabama, Arizona and North Carolina have passed laws barring local jurisdictions from adopting higher minimum wages. Other states — mostly conservative states with more liberal cities — are considering doing the same. Minimum wages aren’t the only target; state legislatures are also trying to prevent cities from requiring companies to offer paid sick leave and other benefits.

Backers of these so-call pre-emption laws argue that businesses shouldn’t have to navigate different rules every time they expand into a new city or town. That argument makes sense when it comes to safety rules, environmental regulations or occupational licensing requirements — construction isn’t any more dangerous in Phoenix than in Tempe, after all. But the minimum wage is a different story; the cost of living can vary widely from one city to another, even within a state, so it makes sense for the minimum wage to vary, too.

Stay in (the right) school

For all the recent debate over whether college is “worth it,” higher education remains the best path to the middle class for most Americans. But new reports this week highlighted two important caveats: College is only worth it for those who finish their degrees and who choose the right program in the first place.

I’ve written before about the importance of ensuring that students who start college go on to graduate — students who drop out often struggle to pay back student loans, leaving them worse off financially than if they’d never gone. A new report from Third Way, a Washington think tank, found that many private colleges are failing to help students — and especially low-income students — finish their degrees. According to the report, at the average private, non-profit school (a small minority of all institutions), only 55 percent of full-time students graduate within six years. As Quoctrung Bui of The New York Times illustrated, the schools that enroll the most low-income students also tend to have the lowest graduation rates.

Meanwhile, separate research released this week found that students who attended for-profit colleges ended up worse off on average than if they had never enrolled at all. Using data from the Internal Revenue Service, the researchers found that students who went to for-profit schools are less likely to have a job and earn less money than they did before they started. They also, of course, have significantly more debt. By contrast, associate degree programs at public colleges substantially boosted students earnings.

Number of the week

Consumer spending rose at a 1 percent annual rate in April, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported Tuesday. That’s the fastest growth in more than six years.

Economists cautioned against reading too much into the report, which likely reflected one-time seasonal fluctuations. (For example: Unusually warm weather earlier this spring led to lower utility spending in March, which made April’s more normal spending look stronger by comparison.) But even if April’s jump was a fluke, the underlying trend in consumer spending remains strong. That’s good news given that the manufacturing sector is struggling amid weak global growth.

We’ll get a more up-to-date glimpse of how both the consumer and manufacturing economies are doing in the May jobs report, which will be released this morning. We’ll have our usual coverage later today.

Elsewhere

Eduardo Porter says a universal basic income (a favorite topic around these parts) won’t fight poverty.

“Welfare,” 20 years post-reform, means a lot more than cash payments — and no longer goes only to the poor, writes Krissy Clark. (Meanwhile, Jordan Weissmann argues that welfare reform has failed.)

Economist James Sherk of The Heritage Foundation pushes back againstclaims from liberal groups that workers’ wages aren’t keeping up with their productivity gains.

Bloomberg Businessweek goes deep into the deadly failures at air bag maker Takata.

Fuente original: FiveThirtyEight