The economic glass is still half-full for many Americans.

American Hispanics earn $18,000 less per year on average than their white neighbors.1 Their unemployment rate is nearly 40 percent higher.2Hispanics are less likely than whites to own a home or graduate from college. They are more than twice as likely to live in poverty.

Yet according to a new poll out this week from the Pew Research Center, Hispanics are also substantially more optimistic about their economic future than Americans writ large. (The Pew survey didn’t break out data for non-Hispanic whites.) More than 80 percent of Hispanics say they expect their financial situation to improve in the next year, versus 61 percent for all Americans.

Hispanics’ optimism seems to fly in the face of one of the dominant narratives of this year’s presidential campaign: voters’ economic anxiety. Despite an economy that has, by most conventional measures, improved by leaps and bounds since President Obama took office, Donald Trump and, to a lesser degree, Bernie Sanders have successfully tapped into a deep well of anger and fear about the country’s economic direction. But that anger is concentrated among whites; many minority voters, as the Pew survey shows, are far more optimistic.

A few months back, I argued that voters’ anger stems more from longer-run anxiety than from concern over their immediate economic prospects. Sure, unemployment is low and incomes are rising again, but Americans are worried about slow wage growth, ballooning student loan balances and inadequate retirement savings. Gallup in recent months has shown a divergence between Americans’ relatively positive assessment of their current economic conditions and their increasingly pessimistic outlook.

But for many non-whites, the pattern is the opposite: They are concerned about the present but optimistic about the future. In the Pew poll, Hispanics were sober about their immediate financial circumstances — 40 percent said their finances were in good shape, compared with 43 percent for the public at large — but they see brighter days ahead. More than 70 percent expect their children to be better off than they are. Previous polls have found similar results for other minority groups: According to 2014 data from the General Social Survey, three-quarters of blacks and Hispanics expect their children to enjoy a higher standard of living than they do, compared to just half of whites. A poll commissioned by The Atlantic last fall found that blacks, Hispanics and Asians were far more likely than whites to report that “the American Dream is alive and well.”

That optimism might seem surprising given high rates of unemployment and poverty among Hispanics and, to an even greater degree, African-Americans. But views of the future are heavily influenced by views of the past. It’s hardly surprising that blacks and Hispanics are less nostalgic than whites for an era when they were, explicitly, second-class citizens. In the Atlantic survey, blacks, Hispanics and Asians were far less likely than whites to say that “America’s best days are behind us.”

It’s no coincidence, then, that Trump and Sanders drew their strongest support from white voters. (In the case of Trump, of course, there are alsoother reasons.) Blacks and Hispanics, meanwhile, have voted overwhelmingly for the establishment candidate, Hillary Clinton. It’s important not to overstate the racial voting divide — many younger black voters favored Sanders, for example. But it’s worth remembering that in a year when Trump won the Republican nomination by pledging to “make America great again,” there is a large group of Americans who already think America, or at least its economy, is headed in the right direction.

The nonwhite working class

One other note on demographics and the economy: The Economic Policy Institute, a left-leaning think tank, this week estimated that the working class — which EPI defines as any adult without a college degree — will be“majority minority” by 2032. That’s more than a decade before non-Hispanic whites will be a minority in the population as a whole.

The presidential primary campaign was dominated by talk of the “white working class,” whose well-being promises to be a major theme in the general election, as well. But the EPI report is a useful reminder that whites make up a shrinking share of the working class, by whatever definition you choose. If candidates really want to help lower-income Americans, they’ll have to talk not just about manufacturing in Ohio and coal mining in West Virginia but also about how to create opportunities in places such as St. Louis, the South Bronx and the Rio Grande Valley that are dominated by the nonwhite working class.

Shale gas

Energy giant Royal Dutch Shell announced this week that it would slash spending amid low oil prices. But one big project not on the chopping block: a new petrochemical plant in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, which got the final go-ahead from Shell after years of planning. Locals hope the plant, to be built on the site of an abandoned zinc smelter, will breathe new lifeinto the area’s long-struggling economy.

Shell’s announcement highlights the remarkable durability of the shale gas revolution, which began a decade ago outside Fort Worth, Texas, and spread to Arkansas, Louisiana and Pennsylvania. The initial drilling boom has long since faded because of low natural-gas prices and, until oil prices also cratered, the industry’s preference for producing more oil over less profitable gas. But drilling slowed, production never did; U.S. gas production set a record last year, as it has every year since 2011. The Energy Information Administration expects production to keep rising for the next two and a half decades.

In the early years of the shale boom, many industry insiders thought the impact would be short lived. But as Shell’s new plant shows, companies are increasingly betting that shale represents a permanent, or at least multidecade shift. Other companies are building facilities to export gas overseas in the form of liquefied natural gas. And the power industry has made a dramatic shift toward natural gas and away from coal. In terms of long-term economic impact, shale is just getting started.

Number of the week

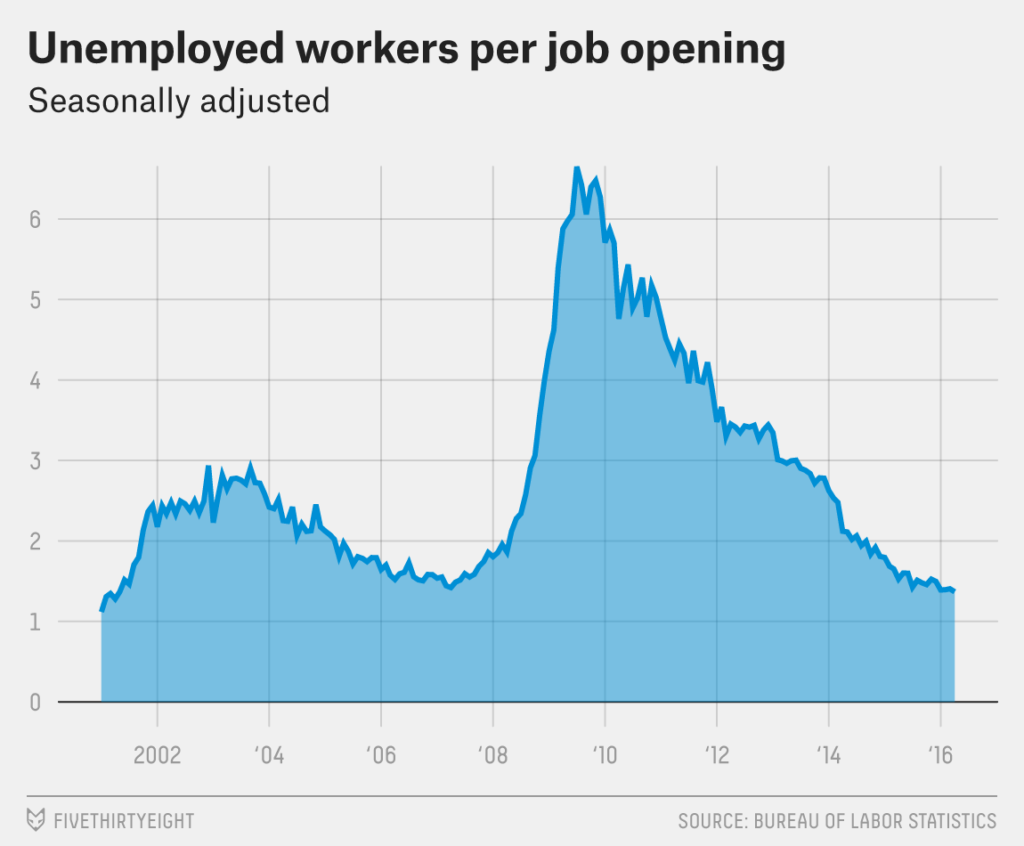

There were 1.4 unemployed workers for every available job opening in April, according to data released Wednesday by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That’s the lowest the ratio has been since 2001 — meaning that, by one measure at least, the job market is better today than at any point during the housing boom. But it would be wise to view that interpretation with some skepticism.

First of all, the official definition of unemployment is relatively narrow, counting only those who are actively looking for jobs. Factoring in people who have stopped looking for work makes the workers-per-openings ratio look a bit less rosy. But only a bit. Even under the broadest possible definition of unemployment — counting every adult who isn’t working, no matter the reason — the number of available workers for every job opening is better than its housing-boom peak.

The real problem is on the other side of the ratio: job openings. Back in 2006, companies hired about 1.2 workers for every job opening they posted.3Today, that figure has fallen below 1 for the first time on record.

Why aren’t companies filling their open jobs? One popular theory is that they can’t find workers with the right skills. That may be true in some industries such as construction, but there’s little evidence for it on a broader level; in particular, wage growth has been weak, which suggests companies aren’t being forced to raise pay to attract qualified workers. More likely, there has been a shift in the way companies recruit workers, perhaps because online job sites have made it easier for companies to post positions they aren’t committed to filling. But whatever the explanation, there’s reason to think a “job opening” doesn’t mean what it used to.

Elsewhere

Conor Sen says that after a quiet few years, housing is “about to reassert itself as the main driver of the U.S. economy.”

Laura Stevens reports that for the first time ever, Americans bought more goods online than in stores in 2015.

Noah Smith discusses what Silicon Valley’s upcoming basic-income experiment can and can’t teach us.

Fuente original: FiftyThirtyEight