A decade after the collapse of the housing market set into motion a series of events that brought the national economy to its knees, the country is mired in another housing crisis.

A decade after the collapse of the housing market set into motion a series of events that brought the national economy to its knees, the country is mired in another housing crisis.

We’re out of the frying pan of speculative excess and into a subtler and more insidious problem of chronic undersupply. A country that’s always prided itself on open spaces, abundant housing, and ample opportunity now has too few homes and is building too few to keep up with its needs. That’s the bad news.

The good news is that unlocking the stuck glue of housing supply would solve multiple economic problems at once. Most obviously, people could have more and better places to live. But beyond that, a surge in house building would also be the jobs engine the country needs — decently paying blue-collar work that isn’t going to be outsourced to China.

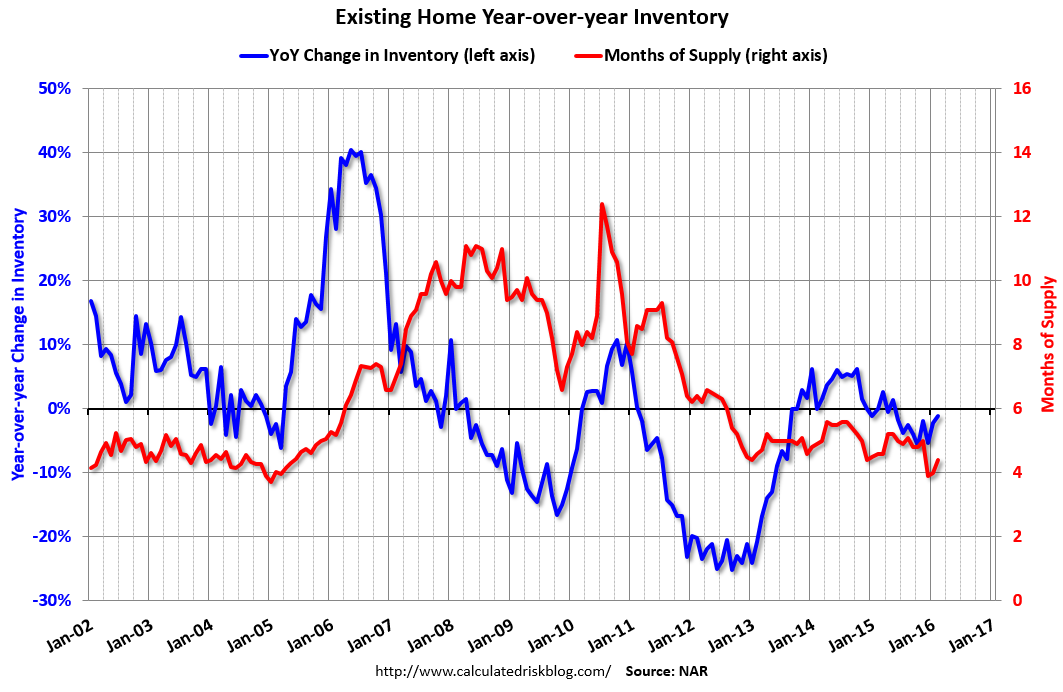

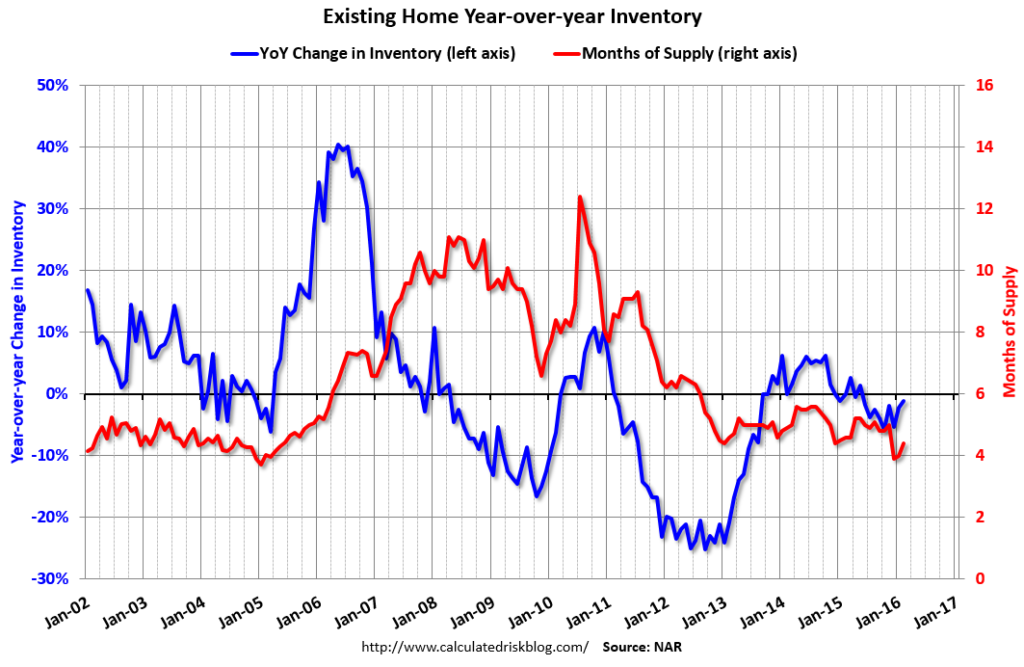

Housing inventory is at a historic low

The National Association of Realtors keeps track on America’s inventory of houses for sale, which can be expressed in terms of «months of supply» — in other words, if no new homes came on the market how quickly we would run out entirely.

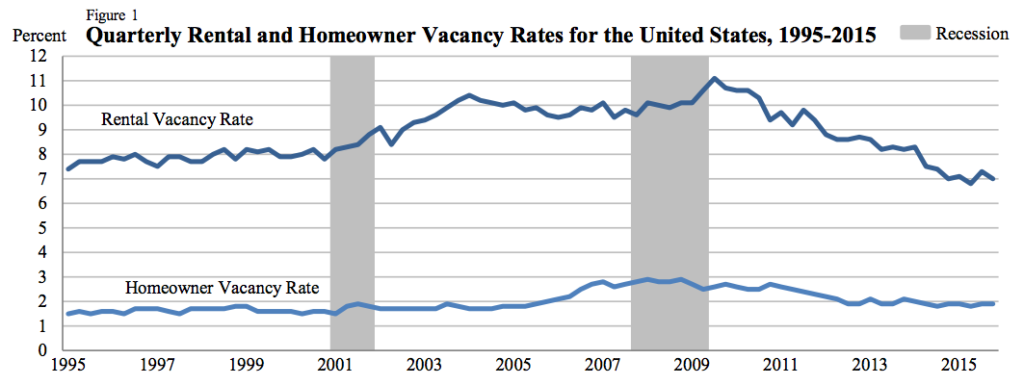

At the same time, the vacancy rate for owner-occupied homes, which soared during the crash, has now normalized, while the rental vacancy rate has plunged to a very low level.

At the same time, the vacancy rate for owner-occupied homes, which soared during the crash, has now normalized, while the rental vacancy rate has plunged to a very low level.

This means rising rents, which squeeze households’ ability to spend on other goods and services. And the increase in rents also shows up in economy-wide inflation indexes and discourages the Federal Reserve from taking steps to boost overall national income growth.

Short inventory isn’t spurring a construction boom

The good news ought to be that a low level of housing supply leads to a boom in house building, which puts people to work and eventually ameliorates the shortage.

But it’s not happening. Instead, construction of new homes remains at an abnormally low level.

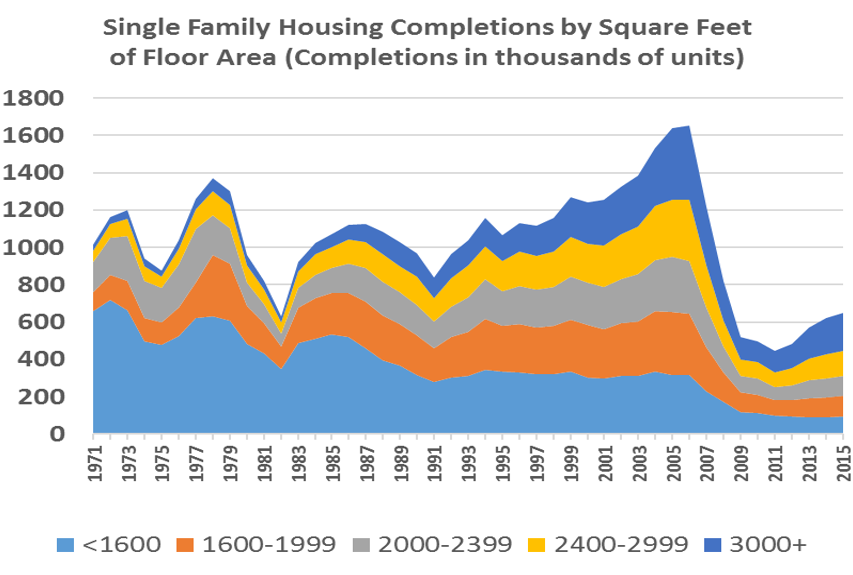

Construction of McMansions has rebounded strongly, but overall construction remains in a fairly profound funk even as the population today is much larger than it was back in the 1970s.

So what’s going on? The basic story seems to be that after years of financial crisis and recession, a large share of Americans are simply too burdened by low wages, past foreclosure, depleted savings, and overhangs of other debts (student loans, medical bills, etc.) to buy starter homes. And while investors were willing to pick up vacant or bank-owned single-family homes for pennies on the dollar during the peak slump years to operate them as rentals, nobody is excited enough about the business of operating single-family rental homes to actually go out and build vast new tracts of modest-size single-family homes destined for the rental market.

The houses we need to build

Of course, people who, for whatever reason, are not prepared for homeownership have long been with us. Traditionally, the solution has been to build dwellings for them that are not detached single-family homes.

In the modern day, that means apartment buildings and mobile homes. But while apartment construction has risen dramatically over the past several years, it remains hampered by the basic reality that it is illegal across huge swaths of the country. Suburban counties are defined by exclusionary zoning rules that bar the construction of multifamily housing, and from Seattle to San Francisco to Washington and beyond, even in many central cities, vast tracts of land are set aside exclusively for the development of detached single-family homes.

For areas of the country where land is cheap, mobile homes are the optimal solution, but here, too, snobby zoning rules prevent delivery of such homes across much of the country.

Obviously, constructing cheaper dwellings is in some respects a poor substitute for giving everyone enough wealth and income to get a mortgage on a single-family home. On the other hand, relaxing regulatory constraints to allow for more multifamily and mobile homes would itself be a way to create more good-paying jobs. The 2016 campaign has featured multiple rounds of unrealistic promises to «bring back» manufacturing jobs lost to China. But similar blue-collar work could be created without trade wars.

All we need to do is allow market demand to fill Palo Alto and Bergen County and Chevy Chase with rowhouses and triple-deckers and other «missing middle» housing forms while allowing high-rise construction in the limited number of places where it’s economically viable.

Fuente original: Vox